This title of this entry might be more expansively and appropriately called "ruins, ghosts, wasted lives, and a glimpse of hell." The small island of Peleliu, part of the Palaus Islands, is the site of a very bloody, once highly controversial, and largely forgotten battle of the US island-hopping campaign against the Japanese Empire from September-November 1944. The US military anticipated resistance would be light and the small island (6 miles long and 2 miles wide at most) would fall in about four days. Instead, the invasion turned into a 71-day nightmare. The US would suffer over 8,000 casualties, 6,700 of them from the 1st Marine Division. Countless more marines and soldiers would fall to combat exhaustion, heat stroke, and tropical illnesses in the miserable conditions. Estimates vary, but somewhere between 10,000 and 14,000 Japanese troops would also perish, most of them buried or simply covered up in the caves and positions they died in. See this May 2015

LA Times article on some of the most recent efforts to recover these remains.

At Peleliu, US forces were rudely introduced to new Japanese tactics for defending islands. Following the losses of islands in the Solomons, Gilberts, and particularly the Marianas, the Japanese decided to no longer base their island defenses on defeating the invasion forces on the beaches. Instead, they would continue to offer some resistance at the beach, but concentrate on in-depth defenses further inland, hoping to cause severe attrition amongst the attackers. Essentially, Japanese forces would fight for time and hope that heavy casualties would weaken the will of the US. Peleliu's terrain offered a model for these type defenses, which would provide the basis for the defenses of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. The Japanese commander on Peleliu would resist the invasion, but base most of his defenses in and around the island's highest ground, the Umurbrogol, a collection of rugged coral-covered hills, steep ridges, sharp peaks, deep defiles, and sheer walls, which overlooked the remainder of the island, including its airfield, the objective of the US attack. The Umurbrogol also contained hundreds of limestone caves, which would serve as ready-made defensive positions. The Japanese improved these caves, added connecting tunnels and more defenses, making the entire area a massive honeycombed defensive position with interlocking fields of fire manned by well-trained infantry, plus naval and air force personnel, armed with large numbers of machine guns, other automatic weapons, mortars, and artillery. Once completed, the Umurbrogol, which would earn the nickname "Bloody Nose Ridge," would be one of the most formidable defensive positions of the entire war.

|

| Pre-invasion aerial photograph of Peleliu. |

While historians continue to spar over the issue, the sad truth is that the battle probably never should have taken place because by September 1944 the island had lost any strategic value it once held. The stated reason for the operation was to clear the right flank of Douglas MacArthur's planned invasion of the Philippines and provide an air base to support that operation. However, US carrier-based air operations had already largely destroyed Japanese air capabilities in the Palaus, and Japanese forces there thus lacked the means to interfere with any US operations against the Philippines. In addition, the island's airfield never played much of a role in subsequent US operations, certainly not one that could justify the enormous costs of taking it. The losses too caused controversy. The 1st Marine Regiment, for example, in the first two days of fighting suffered around 1,000 casualties, or about 30 percent of is strength. It would eventually take over 1,800 casualties in just five days of action before being pulled out, decimated and exhausted. US units in World War Two were usually taken out of combat once they hit 15 percent losses, yet the regimental commander ("Chesty" Puller) and the divisional commander (William Rupertus), kept pressing their depleted Marine units to attack, while refusing to call in readily available Army troops, denigrating the capabilities of the soldiers (81st Infantry Division) and thinking falsely that the Japanese were on the verge of breaking.

Today, despite a growing number of books and a couple of featured episodes in the HBO series "The Pacific," Peleliu is largely forgotten, overshadowed by more well-known battles, such as Iwo Jima and Operation Market Garden ("A Bridge Too Far") in Europe. The island is remote, rather sleepy, and home to only about 500 people. The battlefield, once ravaged by war, is now covered again by a dense carpet of tropical vegetation. The Umurbrogol, almost devoid of vegetation in 1944 because of US bombardments and napalm, is now almost unrecognizable. Even the old airfield, where hundreds of marines once conducted a mass World War One-type assault across its exposed ground under heavy Japanese fire, is now largely reclaimed by Mother Nature. Visitors who take the time to go to Pelelui, however, will be well-rewarded with a fascinating view of a unique battle. The invasion beaches are easily accessible, as are several monuments to US and Japanese marines and soldiers, and a number Japanese bunkers and caves. Relics of the battle, including tanks, amphibious landing craft, artillery guns, small arms, shell casings, and basic soldier equipment litter the island. The Umurbrogol is a tougher area to penetrate, but with a map, a local guide, sturdy boots, and a willingness to get a little dirty and accumulate a lot of body sweat, one can venture into its forbidding terrain for a rewarding experience of examining dozens of Japanese cave position and marveling at the difficulties faced by US marines and soldiers charged with taking those positions some 70 years ago. One can also get a feel for the horrible conditions their Japanese foes fought under in defending their Umurbrogol stronghold.

We spent a little over two full days on Peleliu, sandwiched by time in Koror and exploring the waters around the Palaus Islands, which are world-famous for their underwater diving locations. Though the waters were absolutely stunning, I was frankly more interested in Peleliu than watching fish (though we did see several sharks which was pretty cool). I had long hoped to make it to Peleliu, thinking that if I visited one Pacific war island battlefield, this was the one I wanted to see. So, we packed in quite a bit of exploration into those two days, taking in a considerable portion of the battlefield, including key sections of the Umurbrogol. I would like to have seen more of the Umurbrogol, but access to the more remote areas, already difficult because of the dense vegetation and lack of trails, is now further exacerbated by the damage from a typhoon that hit the island last year (an old trail that led up towards Walt's and Boyd ridges, for example, was completely blocked). Weather conditions were also a factor. When the Marines conducted their assault in September of 1944, the temperatures were as high as 115 and many marines fell to heat exhaustion (there was also very little water on the island). Thankfully, when we hit the island in September 2014, the temperatures were only in the upper 80s, but the air was super thick with humidity. We must have lost a few gallons of sweat in exploring the hills of the Umurbrogol, where the air was still and stifling, particularly in the caves and tunnels. Even rain showers provided little relief. Without plenty of water, we would have been heat casualties as well. One could only imagine what it was truly like for the Americans and Japanese fighting in those conditions.

This will be a long entry because I want to do a comprehensive look and do it all at once, but no blow-by-blow accounts here. Just a modern-day look at what must have been in 1944 something akin to fighting in what author Derrick Wright called "the far side of hell."

|

| LIFE magazine artist Tom Lea's iconic portrait of a Marine on Peleliu with the Umurbrogol rising in the background, Marines Call It That 2,000 Yard Stare. Mr. Lea accompanied the Marines during their assault. "As

we passed sick bay, still in the shell hole, it was crowded with

wounded, and somehow hushed in the evening light. I noticed a tattered

Marine standing quietly by a corpsman, staring stiffly at nothing. His

mind had crumbled in battle, his jaw hung, and his eyes were like two

black empty holes in his head. Down by the beach again, we walked

silently as we passed the long line of dead Marines under the

tarpaulins." See more of his Peleliu art here. |

Our Host

|

| Following Godwin into the Wildcat Bowl. |

Before we go into the tour, I want to recognize Godwin, our host and guide for our time on Peleliu. We hitched a ride on one of his boats from Koror to Peleliu and stayed in his beautiful Dolphin Bay resort, run by his lovely wife, Miyumi. Godwin also drove us around the battlefield and guided us into the formidable terrain and caves of the Umurbrogol. He knew all the sites we asked him about like the back of his hand and was more than accommodating in taking us wherever we wanted to go...or telling us that the terrain was simply too rough to tackle for the amount of time we had.

The Invasion Beaches

The three regiments (1st, 5th, and 7th) of the 1st Marine Division landed on Peleliu on 15 September 1944 with the 1st on the left hitting White Beach, while the 5th (center) and 7th (right) hit the Orange beaches.

|

White Beach, landing site for the 1st Marine Regiment. The 1st Marines took heavy casualties here, primarily from "the Point," the part of the beach that extends out into the ocean in the background. Japanese artillery and machine guns at

the Point wreaked havoc on amphibious assault landing craft and exposed marines. The Point was actually a low coral-covered ridge that extended for several hundred meters inland and was honeycombed with defensive positions the Japanese blasted into the coral. One Marine officer described the area as a "rocky mass of sharp

pinnacles deep crevasses, tremendous boulders. Pillboxes, reinforced

with steel and concrete, had been dug or blasted in the base of the

perpendicular drop to the beach. Others, with coral and concrete piled

six feet on top were constructed above, and spider holes were blasted

around them for protecting infantry." Marine maps did not show the ridge, nor did pre-invasion aerial photographs, so it was an ugly surprise. |

|

| The view of White Beach from the Point. |

|

| Japanese bunker at the Point facing the beach. This particular casemated bunker, which probably held a 47mm gun was responsible for many of the 1st Marine casualties and the destruction of perhaps six amphibious assault landing craft. It was perfectly placed for pouring fire into the flanks of the invasion forces. If you watch the Peleliu invasion episode of "The Pacific," this bunker is featured when Robert Leckie's amphibious assault craft comes ashore (although Leckie did not land near the Point). The bunker was once part of at least five such positions in the vicinity, according to author Bill Sloan. They were not even scratched by naval pre-invasion bombardment, even the though the Navy commander claimed he had run out of targets. |

|

| A close up. Note the mass of coral covering the ground. No place to dig in and much of it is razor sharp as my shoes and hands can attest. Said one marine, "Around this place there's nothin' but sharp coral. I mean, you get down on your hands and knees, you're getting cut. And grenades are going off. And each time this coral is shattering in small bits and it peppers you. I guess it would be as if somebody turned a sandblaster on you." Also note the pitted concrete, attesting to the volume of fire the Marines directed towards the position. |

|

| Visible in the left center of this photo (taken from the Point and

looking back towards White Beach) is a plaque to Captain George P.

Hunt, whose K Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines took the beach end of

the Point and then held off several Japanese counterattacks for some 30

hours. Afterwards, only 78 men remained standing out of his 235-man company. |

|

| Looking inland from the Point. The terrain, where hundreds of Japanese soldiers and American marines once fought at close range for more than 24 hours is completely covered with heavy vegetation. The Japanese commander committed one of his battalions (about 1,000 men) to defend the beaches, most of them in the area around the Point. Another battalion was used to counterattack the landings. Marines counted some 500 Japanese bodies scattered around the Point once fighting there concluded. |

|

| White Beach 1 and 2 on 15 September 1944 with the beach end of the Point clearly visible at the top. |

|

| Marines dig in on White Beach. The Point is the high ground in the background. |

|

| Further down White Beach is the rusted hulk of an LVT, or Landing Vehicle Tracked, wrecked during the invasion and now a permanent fixture of the island, complete with a massive tree growing through its skeletal frame. The commander of the 1st Marines, whose own assault craft was hit by "four or five shells" after he scrambled out of it, said upon landing that, "I looked down the beach and saw a mess--every damned amtrac in our wave had been destroyed in the water....or shot to pieces the minute it landed." |

|

| Orange Beach, landing sites for the 5th and 7th Marines. This particular area was the right flank of the 7th Marines. In 1944, there was an unnamed island situated where the peninsula now sits in the background. This island poured deadly fire into the right flank of the 7th during the invasion. As many as 60 amphibious assault craft were knocked out in the water or on the beach by fire from the flanks of White and Orange beaches, as well as artillery positioned in the Umurbrogol. |

Moving Inland

Once the beaches were secured, the Marines moved inland. The 1st Marines struggled with the high ground extending inland from the Point, but eventually seized the area and moved toward the northern end of the airfield where the forbidding Umurbrogol awaited. The 5th Marines attacked across the southern part of airfield, while the 7th Marines turned right to seize the southern part of the island.

|

| The 1st Marines ran into this massive blockhouse as it pushed inland on the 2nd day of the invasion. 14-inch guns from the battleship Mississippi were used to neutralize it when the thick walls proved too tough for infantry. Today it is a museum (more later). |

|

| Same shot in 1944. Nearly all the Japanese soldiers in the building were killed by just the terrific concussion of the giant battleship shells. |

|

| All that remains of the old airfield is this weedy strip. Marines from the 1st and 5th Regiments attacked across it on the second day of the invasion. Those of the 5th would have crossed this part. Eugene Sledge ( K Company/3rd Battalion/5th Marines), in his personal account of the war, "With the Old Breed," said crossing the airfield was "the worst combat experience [he] had during the war." The Japanese could observe the airfield from the heights of the Umurbrogol, (faintly visible in the background) and poured machine gun and artillery fire on to the marines assaulting across it. Says Sledge, "The sun bore down unmercifully, and the heat was exhausting. Smoke and dust from the barrage limited my vision. The ground seemed to sway back and forth under the concussions. I felt as though I were floating along in the vortex of some unreal thunderstorm. Japanese bullets snapped and cracked, and tracers went by me on both sides at waist height. This deadly small-arms fire seemed almost insignificant amid the erupting shells. Explosions and the hum and the growl of shell fragments shredded the air. Chunks of blasted coral stung my face and hands while steel fragments spattered down on the hard rock like hail on a city street. Everywhere shells flashed like firecrackers." |

|

| The remains of a Japanese Type 95 tank, which took part in a failed Japanese tank-infantry counterattack across part of the airfield against the 1st and 5th Marines late in the afternoon on the first day of the invasion. The Type 95 was hopelessly obsolete by 1944, and the attack was beaten off with practically all the tanks destroyed and approximately 500 Japanese infantry killed. However, the well-disciplined attack illustrated to the Marines that they faced a tough and determined opponent. |

|

| Bombed out ruins of Japanese headquarters/administrative buildings on the north side of the old airfield. The 1st Marines seized this area. |

|

| Another building depicted in one of "The Pacific" episodes, although perhaps a bit over dramatized because most of the fire described by marines like Sledge came from positions in the Umurbrogal, not these buildings. The Marines rooted out Japanese defenders from here on the second day of the invasion. |

|

| Bunker protecting the island's power plant. |

|

| There are numerous old wrecked LVTs strewn around the island. Their stories are mostly unknown. |

|

| Another destroyed LVT. |

|

| The remains of an unfinished position behind the beaches, probably for anti-aircraft guns. |

|

| Same position in 1944. |

|

| Once the 7th Marines exited Orange Beach, they turned south and attacked Ngarmoked Island, which was not really an island since it was attached to Peleliu by a narrow isthmus. The place is supposedly still dotted with old Japanese defensive positions, including one taken by a young marine who won the Medal of Honor for taking several positions and killing approximately 50 Japanese soldiers by himself. The 7th claimed to have killed over 2,600 Japanese in this sector with the loss of 500 marines. There were no prisoners taken. This caused some concern because the south was supposed to be the easiest part of the operation. Unfortunately, due to damage from a typhoon which struck the island last year, the old access road into Ngarmoked is impassable and the "island" itself is a tangled mess of uprooted trees, according to our guide. |

|

| The "Lady Luck," a tracked amphibious assault craft, which drove over a pesky Japanese gun emplacement during the battle, left to rust away in the jungle. |

|

| The Lady Luck in 1944 and the Japanese gun it destroyed. |

Museum. The museum was small, but contained a rather impressive array of battlefield relics.

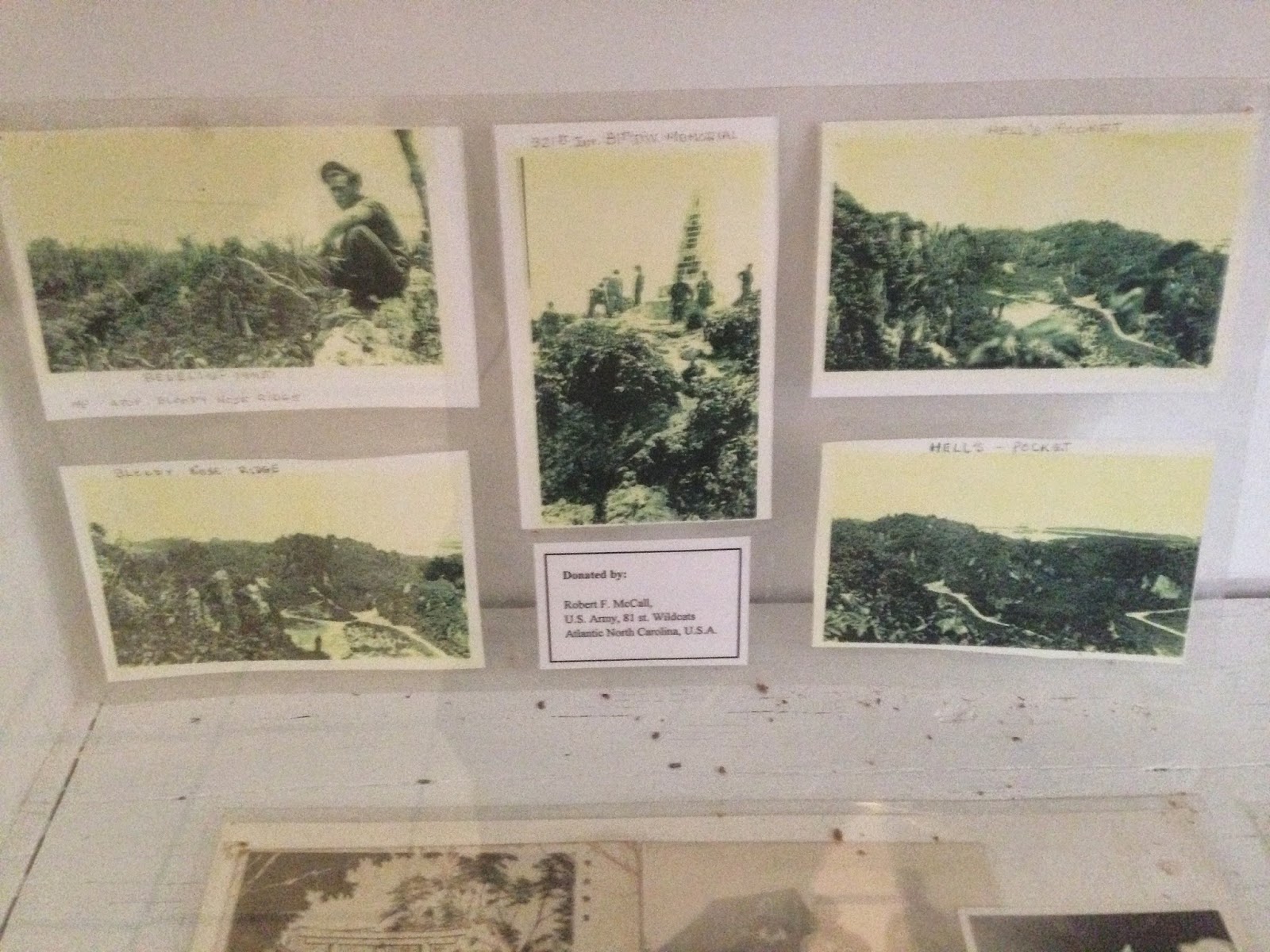

These last two photos I thought were particularly noteworthy. They are from US soldiers who spent time on the island and decided to donate their personal photos to the museum.

The Umurbrogol

Within a couple of days of the invasion, the Marines were butting up against the Umorbrogol and discovering that the real fight was only just beginning, this despite already having suffered a few thousand casualties and killing a substantial portion of the Japanese garrison. The 1st Marines would be the first to enter the Japanese stronghold, beginning with some high ground (hills 160, 200, and 210--the hills were named for their elevation) that gave the Japanese the ability to see a large part of the southern end of the island and direct artillery fire on the US-occupied airfield and the landing beaches where supplies poured ashore. Marines would battle their way up these hills, engage in close-quarters combat, and take heavy losses. Unfortunately, securing the crest of one hill or ridge only put the marines under fire from the next one, setting a pattern for the rest of the fight for the Umurbrogol "Pocket," where an estimated 2-3,000 determined Japanese troops prepared to defend an area about 1,000 yards long and 500 yards wide. Here, they would hold out from the end of September until almost the end of November, determined to take as many American lives as they could before succumbing. Once the 5th and 7th Marines secured other parts of the island, they too would take their part in subduing the Pocket, as would Army troops from the 81st Division. All would experience and long remember the horror of such infamous places as "the Five Sisters," "the Five Brothers," "Death Valley," "the China Wall," "the Wildcat Bowl," "Walt's Ridge," and "the Horseshoe." Judging by statements from the marines who fought on these hills and had previously fought on Guadalcanal and would later fight on Okinawa, this was their toughest fight of the war. To get an appreciation of the terrain, here are a few shots taken of the Umurbrogol during and after the battle, followed by our photos. Our photos fail to capture the breadth of the originals simply because there are few vantage points from which to take in the vegetation-covered entire area.

|

| Overhead shot of the Umubrogol. Note three primary ridges and valleys. From left to right: the very narrow Death Valley, China Wall with the Five Sisters on its southern end, Wildcat Bowl, the Five Brothers ridge, the Horseshoe (the one with the body of water), and Walt Ridge (also known as Hill 100). Off to the north of these terrain features are more places where men fought and died, like Boyd Ridge, Baldy Ridge, and Hill 140. Marines named the whole area "Bloody Nose Ridge," although one marine said another name given was "'Prostitute Ridge,' because we climbed off and on it so many times." |

|

| From a different direction. This shot also includes Hills 200 and 210 (lower left) and Old Baldy (the large hill just above the tent line). The 1st Marine history described the terrain as "as contorted mass of decayed coral, strewn with rubble, crags, ridges, and gulches thrown together in a confusing maze...it was impossible to dig in...the jagged rock slashed their shoes and clothes, and tore their bodies every time they hit the deck for safety...Into this the enemy dug and tunneled like moles; and there they stayed to fight to the death." Of note, while the battle for the Pocket continued, Army and Army Air Force service troops moved in to occupy the airfield and established the village of tents you see in this photo. Front-line troops tell a number of stories of rear echelon troops entering the battle zone looking for souvenirs, some of whom lost their lives while doing so. |

|

| The Five Brothers. Said a marine years later, "I remember it as a series of crags, ripped bare of all standing

vegetation, peeled down to the rotted coral, rolling in smoke, crackling

with heat and stinking of wounds and death. In my memory, it was

always dark up there, even though it must have blazed under the

afternoon sun, because the temperature went up over 115 degrees, and men

cracked wide open from the heat. It must have been the color of the

ridge that made me remember it as always dark--the coral was stained and

black, like bad teeth. Or perhaps it was because there was almost

always smoke and dust and flying coral in the air." |

|

| The "Horseshoe," which the 81st Division called "Mortimer Valley." Walt Ridge is on the right. The Marines originally called it Hill 100. A company of the 1st Marines attacked it on the third day of the invasion. The 90-man force (it had landed with 235 men) was whittled down to 25 men by the time they finally seized the top of Hill 100 on day four, only to realize it was solid ridge (their maps were wrong). Upon reaching the top, they immediately came under more heavy fire and counterattacks from other parts of the ridge and were practically surrounded. They fought all night, withdrawing early in the morning with only 9 men unscathed. |

|

| Another view of the Horseshoe, this time from the opposite (north) end with Walt's Ridge on the left and the Five Brothers on the right. One marine said the terrain was "like the surface of a waffle iron, only magnified about a million times." |

|

| The Wildcat Bowl, looking south. Visible at the bottom of the cliff face are Japanese positions, although additional hidden positions probably litter the upper parts of the sheer wall. According to a 1st Marine Division general, "...the Japanese maintained relays of snipers, prepared paths, and machine gunners, or shafts from caves below. The approaches were few and so exposed that a minimum number of men could stop a much larger force. Thousands of rounds of artillery, mortars, and bombs had poured in and around the pocket...but the Japanese inside the caves were untouched." This last part was not exactly true. I will touch upon it later, but the Japanese in the caves led a terrible existence, with many dying from concussions from the explosions, burned to death by flamethrowers, suffocated, or simply buried by collapsed caves or caves sealed by US bulldozers. |

|

| Great shot of the sheer nature of the ridge walls. |

|

| An armored bulldozer closes up a cave. |

|

| A favorite and probably most effective method for destroying cave positions: Long-range flamethrower. |

|

| Tanks and infantry move into "the Horseshoe." |

|

| Tanks and infantry attack the Five Brothers. |

|

| Tanks and infantry under fire in the Horseshoe. |

|

| More shots of the ridges and the caves. |

|

| The Horseshoe today with Walt Ridge on the right. It was almost amazing how the vegetation had returned to consume everything. |

|

| The Horseshoe with the Five Brothers in the left background. |

|

| Two of the Brothers. |

|

| View from atop the Five Sisters, looking back over the airfield with the landing beaches in the right background. In the trees below is the entrance to Death Valley, plus hills 200 and 210. |

|

| Looking down from the Five Sisters on the Horseshoe, with the Brothers on the left. |

|

| Entrance to the Wildcat Bowl (it stretches off to the left). |

Hills 200 and 210. Japanese positions on these two hills caused many marine casualties,

but when the 1st Marines seized them, the Japanese could no longer see

the airfield or beaches, thus eliminating their ability to target them

with artillery or mortar fire.

|

| Hills 200 (left) and 210 (right). The Japanese commander has his command post in this area until driven out by advancing marines. |

|

| Marines tell of a couple of hidden guns such as this one inflicting heavy casualties on troops attacking hills 200 and 210. |

|

| A lot of marines fell in this area. |

|

| Heading into what is thought to be a Japanese ammunition bunker under Hill 200 because contains ammunition carts, among many other rusted pieces of military equipment. |

|

|

Death Valley is probably no more than 75 yards across at its widest point. On one side, it has the forbidding "China Wall," the side of a ridge so named because of its verticle 200-foot walls, which are best suited for mountain climbers, not marines and soldiers. It was honeycombed with multiple layers of Japanese defensive positions. On the other side was a lower and not quite so steep ridge with fewer, but still deadly, defensive positions. Death Valley was perhaps the toughest area to clear for the marines and soldiers and was the last bit of the Umurbrogol to be captured. It also held the last Japanese holdouts, including their commander, Colonel Kunio Nakagawa.

|

| Heading into Death Valley. China Wall on the right. |

|

| There is a loop trail into Death Valley. |

|

| Snapshot of the terrain. |

|

| Japanese cave in Death Valley. Some were small, fit for one or two men, while others could fit dozens of men and multiple weapons systems. |

|

| Positions like these dotted the cliff sides. They only provide a partial look at the original positions, however, as many were covered up during the battle by dozers and explosives and afterwards during the cleanup. Japanese cross-fire across the valley was deadly. Marines and soldiers assaulting one position were often exposed to other hidden positions directly across the narrow defile. |

Nakagawa's last command post.

|

| After its capture by the 81st Division in late November. |

|

| And today. The entrance is at the top of the cut in the far center of the photo. |

|

|

| Up the cut and down into this defile. |

|

| And through another cut to the cave. A very well-concealed and protected position. |

|

| Old mortar shells laying around. Complete shells and the fragments of many others were everywhere it seemed. |

|

| Cave where Nakagawa burned the regimental flag, placed his remaining 56 men under the command of a captain, told them to scatter into guerrilla bands, and committed suicide. The men who scattered were soon killed. It was the end of any organized resistance, although there were holdouts. The last men did not surrender until 1947. |

|

| The cut went completely through the ridge. |

|

Across from Nakagawa's cave was a communications cave, judging by the remnants of radios scattered about.

|

|

| Munitions, like these collected shells, were scattered about the valley. |

|

| A couple positions in the China Wall. Some of the entrances were protected by log revetments, others by coral-filled oil drums. |

|

| Remnants of a Japanese machine gun. |

|

| An old Japanese bicycle. These were the Japanese mode of transportation around the island. |

The Five Sisters were another group of rugged knobs sitting atop a ridge. They figure prominently in the histories of the battle.

Japanese soldiers would hold out in its caves until almost November. Today, it is known for an observation platform which sits on top of one of the Sisters and several monuments.

|

| Recognizing a pilot shot down over the Umurbrogal. Aircraft taking off from Peleliu's airfield that flew missions supporting the attacks often did not even raise their landing gear before dropping their ordnance. |

|

|

| Napalm strike on the Five Sisters. |

|

| Monument on top of the Sisters to the 323rd Regiment, a unit of the 81st Division, which participated in the reduction of the Umurbrogol pocket. |

|

| Monument to the Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen who fought and died on Peleliu. The monument lists all the Japanese military units that fought and perished on the island. About half the Japanese troops on the island were from the 14th Division, which deployed from the wind-swept steppes of Manchuria to the tropics of the Palaus Islands in April 1944. There were also about 4,000 Imperial Japanese Navy personnel on the island. Of the garrison, only 202 were taken prisoner (although a handful of soldiers continued to trickle down out of their hiding places in the hills until 1947), and of these only 19 were

Japanese soldiers. The remainder were Korean and Okinawan laborers who filled out Japanese construction battalions. |

|

| And a Japanese shrine dedicated to the dead. Most of the bodies were never recovered, although over the years, the Japanese government has sent delegations to the island to recover remains. |

|

| Not far away is a monument to the 1st Marine Division, including its 8 members who won the Medal of Honor in the fight for Peleliu. |

|

| The story is that the Japanese did not have any ammunition for this formidable 200mm coastal defense gun. Our guide told us there was another such gun in a cave on the northern part of the island. |

Wildcat Bowl. The 81st "Wildcat" Infantry Division named this area because it spent a considerable amount of its time in the Umurbrogol pocket assaulting positions in its confines. The terrain is similar to Death Valley, but the valley floor is wider.

|

| There is a foot path part way up into the Wildcat Bowl. |

|

| Japanese position, well-hidden even today. |

|

| Aerial bomb laying on the valley floor. |

|

| Monument commemorating Nakagawa's last command post, except it is in the wrong place. His last command post's location in Death Valley is well-documented. We (and our guide) thought this might have been an interim command post after he was driven out of the Hill 200/210 area. |

|

|

| Captured cave in 1944. Author Bill Ross, quoting an apparent marine intelligence officer, says Nakagawa had a command post in the Five Brothers ridge. It had a very narrow entrance, but had a large interior with several levels, including a "balcony" for the colonel. "The installation had most of the comforts and conveniences of permanent quarters: wooden decks, electric lighting, radio and telephone communications equipment, a well-equipped galley, and partitioned quarters with built-in bunks." Boy, what a fascinating cave this one would be to explore, but alas, I suspect the entrance was closed up long ago. |

|

| Buried Japanese artillery piece, probably covered over by a bulldozer during the fighting. Most of the fighting cave positions were small, like this one. There was no exit, so it is assumed the soldiers defending it did so until killed. Many of the caves we discovered were small and U-shaped, which gave the defenders the option of shifting positions, but we could find no discernible exits. Other caves, however, clearly branched off into tunnels and additional chambers. Some of them went all the way through the ridges. |

|

| Remnants of another Japanese artillery piece. |

|

| With live ammunition still laying nearby. |

|

| "The hospital cave." This was a large cave with a number of rooms and passageways and went all the way through the ridge to come out on the other side. It was rather eerie. The bottom of the cave was filled with water and muck. Many bats hung from the ceiling. The air was steamy, stifling (we were pouring sweat), and putrid. It almost seemed as if death still hung in the air. Certainly, one could sense the cave was once a place of suffering and death. Superstitious individuals would no doubt be convinced the ghosts of the many dead remained. Evidence of its former role lay scattered all about, including metal frames of hospital beds, medicine bottles, pieces of what looked to be bandages, and a few bones. This cave, like most of the others we entered, also contained the remnants of soldiers at war, including canteens, gas masks, cooking ware, ammunition pouches, rusted bayonets and helmets, expended cartridges, ammunition, mess kits, and even toothbrushes. A majority of the caves also all seemed to have many empty beer and sake bottles scattered about. Peleliu's lack of water (water was a problem for the Americans early on as well) and the US destruction of the Japanese garrison's water supply probably led the Japanese soldiers to drink lots of beer. Some no doubt got drunk before going off to die. |

|

| Our cameras were not the best for taking photos in the dark of the cave, even with flashlights, but perhaps these photos give you a sense of what lay about. |

|

| The Japanese existence in these caves must have been horrible as the battle wound down. Inside the caves, they increasingly suffered from shortages of water, food, and medical supplies. They also faced death by incineration, suffocation, explosives, and gunfire. The Americans came up with novel ways of reducing the positions, including dumping hundreds of gallons of napalm in the caves (600 gallons in one documented case), then igniting it. Long-range flamethrowers mounted on armored vehicles were also a favorite. The flamethrowers not only sent streams of fire far into the caves, but also sucked the air from them, smothering those who were not burned. Many defenders committed suicide. At night, the Japanese soldiers emerged from their caves to infiltrate US positions, conduct attacks, or search for food and water. As the battle neared its end, these efforts became more desperate. |

Other places.

81st Division monument. The Wildcats of the 81st began participating in the Peleliu operation eight days after the beach landings with the arrival of its 321st Regimental Combat Team (RCT) to replace the decimated 1st Marine Regiment. The 81st had attacked the nearby island of Angaur while the Marines landed on Peleliu. The 323rd would help the 5th and 7th Marines seal and then begin reducing the Umurbrogol pocket. At the end of October, the 81st would take over the entire Peleliu operation, and its 321st and 323rd RCTs would finish out the fight. They essentially laid siege to the pocket, building sandbagged positions in a tighter and tighter ring, while running tank-infantry combat patrols into Death Valley, the Wildcat Bowl, the Horseshoe, and along the ridges, each day killing more Japanese with explosives, gunfire, and flamethrowers or simply sealing up the cave entrances with armored bulldozers. From mid-October to the end of the campaign on 27 November, the 81st claimed to have killed 1,300 Japanese and captured 143. It was thankless, difficult, and deadly work, and largely forgotten as the war moved on. The 81st, which appears to have felt slighted by the accolades given to the 1st Marines (the Marines for example, had eight Medal of Honor winners, while the Wildcats had none), suffered about 1,400 casualties on Peleliu and another 1,600 on Angaur. Nearly 2,000 others suffered non-combat injuries or were afflicted with such tropical diseases as amoebic dysentery, yellow jaundice, hepatitis, and dengue fever.

|

| 81st Division monuments and cemetery in 1944. |

|

| The 81st Division monument today. All US personnel were exhumed and sent back to the States or other national cemeteries after the war. |

|

| Ruins of the old chapel seen in the 1944 photograph. |

"Thousand Man Cave." I do not know if this cave in the northern part of Peleliu was ever manned by 1,000 men, but it is large complex and was built and occupied by the Japanese naval construction personnel on the island. Resistance here was in places stiff and to the death, but relatively weak compared to the fighting in the south. The 5th Marines secured this area, sealing up many of the Japanese defenders in their cave complex. What is left of the cave is now an easy to reach attraction for tourists, just down the road from the boat dock, although the only tourists we saw (Chinese) did not go in as we did.

|

| The cave had multiple entrances and multiple levels, although many of the side passages are now blocked or inaccessible. The upper reaches seemed completely blocked. |

|

| Simple tribute amongst the cave's refuse to perhaps a Japanese ancestor who died on Peleliu. In addition to hundreds of sake and beer bottles, we would find bones in this cave as well. |

|

| This cave in particular was covered in very large cave crickets and these odd-looking things, which looked to be a cross between a cricket, a spider, and a crab. Whatever it was, I doubt it had ever seen the light of day. All the caves were infested with bats. Our other companion on the trip, a former marine, who has visited Peleliu several times previously described once seeing a bat fly into a large web in the hospital cave to be quickly killed by a large spider, which he said was about the size of his rather large hands. |

|

| A large bunker outside the cave. |

|

| Tank of the US Army 710th Tank Battalion destroyed by a buried mine (probably an artillery shell--today's IEDs are not a new thing) between the West Road and Death Valley. The tank was returning from firing on Japanese cliff positions in an attempt to save a couple of US Navy officers who were souvenir hunting. Four of the five crewmen, plus a Marine officer riding on top, were killed. The tank now sits on private property, and the local owner, a very nice guy, kindly came out to show us a typed written letter from the crew's lone survivor describing the story and tell us of the visitors he had seen over the years. |

|

| Blockhouse behind one of the beaches the Marines did not storm. |

|

| Ngesebus Island. Ngesebus was connected to Peleliu by a causeway, and was well-fortified by the Japanese, who used it to shell US troops on Peleliu and as a staging area for trying to reinforce the island. The 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines attacked and seized the island about 2 weeks after the initial landings. The bunker Eugene Sledge and his squad attack in "The Pacific" series was actually on Ngesebus, not Peleliu. Our guide says it is still there. |

(This is H writing the conclusion, to give our readers a Japanese-American's perspective of this historic place). Peleliu was hard. I am positive it was harder for the American, Japanese, Okinawan and Korean men who were forced to fight and die there, but 70 years on, it was still hard for me. I have been through many, many battlefields, it is somewhat of a prerequisite to being married to T, but this was my first World War Two in the Pacific battlefield and it hit me harder, and in a more sensitive part of my gut than did Normandy, Verdun, Gettysburg, or even the Vosges forest where the Japanese American 442nd fought against the Germans. Never before have I been forced to face so clearly and closely a place where the country of my birth, the country that has my loyalty and allegiance, faced an antagonist in the country of my ancestry. It shook me to the core. I cried for both sides here, for the Americans who fell, but also for the thousands and thousands of young Japanese men who had no choice but to go to their ugly, horrific deaths after suffering so much in life. The Japanese lost a large part of a generation of men on this tiny coral island and to what purpose. Exactly why did this have to happen? That was the question on repeat in my mind over and over as we slogged through the jungle, rugged hills, caves and beaches. Peleliu is an island full of ghosts, and not many of them are peaceful. It was perhaps fitting then that on the night before we entered the Umubrogol, a terrific ocean squall hit the beach directly in front of our bungalow. I've never experienced another storm like it in my life. Lashing rain, fierce wind, deafening thunder rained down on us, as if to show us that no matter what we experienced during our sanitized visit to the battlefield, it was nothing, simply nothing, compared to what was suffered by the sons, husbands, brothers, grandsons and friends that died on that out of the way, insignificant island in the fall of 1944.

Back to T. Peleliu was not a particularly important battle during the Pacific War, but the place itself is simply fascinating. So much suffering and dying in an area so small and insignificant. To be part of the small number of Americans who have been to the island and tried to picture the intimacy, brutality, and horror of fighting in this tropical paradise is quite the honor. Peleliu was certainly not Normandy, Verdun, or Gettysburg, but it was something I think neither of us will ever forget and probably would not turn down an opportunity to see again.

Last, I would be remiss if I did not note the books that made me smart on the battle of Peleliu and informed this blog entry. All very informative and chock full of good info on a truly unique battle in American and Japanese military history.

|

| Probably the best of the lot in my view. |

|

| Recent addition describing the 81st Division's role in the Palaus campaign. |

|

| Lots of detail and personal accounts. Sloan is a student of the Marines and has written books on their fights on Okinawa and in Korea. |

|

| Great photos and observations by Eric Hammel, another well-known student of the Marines. |

|

|

|

| Very detailed account of the 1st Marine Regiment's nightmare on Peleliu. Lots of anecdotes and a good guide for tracing the 1st Marines' experience there. |

|

| The only English language Japanese writing on Peleliu I've been able to find. It is a novel describing Japanese soldiers during the battle for Peleliu. The "Breaking Jewel" refers to what is known as gyokusai, translated as "the breaking jewel," but referring to the patriotic act of mass suicide in defense of the Japanese homeland. If you want to get an idea of what it was like to be a Japanese soldier on Peleliu, this is it. |

|

| Classic first-hand account of a marine's Pacifc War experience. Peleliu was Sledge's first time in combat and his account is extremely vivid and well-written. We reviewed it in a previous blog entry. |

|

| Official history of the 81st Division. Worth its weight in gold simply for the fantastic photos of the Umurbrogol. |

|

| Published in 1991, it is probably the first attempt by a professional historian to write about Peleliu. Less focus on the details of the battle and more emphasis on the decisions that led to it. |

|

| A very well-done Osprey book with good maps, photographs, and summary of the battle in less than 100 pages. We brought a copy along for reference. |

|

| I've

never been able to "get into" Leckie's style of writing, but there is no denying he was a very good and prolific historian, beginning with his classic memoir. Leckie's experience

on Peleliu in the 1st Marines was cut short by a wound. |