As promised, a few photos and some commentary on the American Civil War Battle of Antietam that took place on September 17th 1862. The day after Thanksgiving this past year (yes, that was a while ago) was unusually warm and sunny, so we took the opportunity to take H's brother and cousin out the the battlefield. H and I have been there before; indeed, I have walked, run, and biked the place numerous times. For her brother and cousin, however, it was a first. Antietam to me is a nicer to visit than Gettysburg. The countryside is lovely, with old farm houses, open fields, rolling hills, and meandering creeks. The small local village of Sharpsburg, which the Confederates used for their name of the battle, is rather sleepy; there isn't much there. Nothing about the village or battlefield resembles the tourist mecca Gettysburg has become.

The battle itself, while not as large or well-known as Gettysburg, also probably was more important in the grand context of the war. Yes, it was the bloodiest day in American military history with casualties of around 23,000, but the reasons were bigger than that. Antietam, not Gettysburg, was the true military and political turning point of the war. Never again would the Confederates be so close to victory. The battle resulted in a tactical draw, but at the strategic level, it was a major Union victory. It turned back a Confederate offensive into Maryland and ended a string of victories by Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Lee's move into Maryland was one of three such Confederate offensives and the only time in the war they were able to make such a concerted effort. By mid-October, however, they would all be turned back.

Lee's was the most important of those reverses and had the largest impact. First, it allowed President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves in the states in rebellion and turning the war from one of bringing the Union back together to one of ending slavery, and with it, the Old South. Lincoln conceived the idea months before, but Federal losses on the battlefield (particularly Richmond and Second Manassas/Bull Run) prevented him from announcing the measure. He needed a battlefield success, and Antietam gave him that. Lincoln issued the Proclamation on September 22nd, and it went into effect on the 1st of January 1863. Second, Antietam ended any chance of Britain or France recognizing the South or intervening in the war. Lee's victories at Richmond and Second Manassas prior to the Antietam campaign got London and Paris thinking the Confederates might be establishing a legitimate nation and were seriously considering recognizing the Confederacy. Antietam dashed those hopes because once the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, it undermined the case for either London or Paris to recognize the Confederacy. Historian James McPherson summed it up best in his book Crossroads of Freedom:

"No other campaign and battle in the war had such momentous, multiple consequences as Antietam. In July 1863 the dual Union triumphs at Gettysburg and Vicksburg struck another blow that blunted a renewed Confederate offensive in the East and cut off the western third of the Confederacy from the rest. In September 1864 Sherman's capture of Atlanta reversed another decline in Northern morale and set the stage for the final drive to Union victory. These were also pivotal moments. But they would never have happened if the triple offensives Confederate offensives in Mississippi, Kentucky, and most of all Maryland had not been defeated in the fall of 1862."

But what about the battle itself? Antietam is not a difficult battle to describe to the drive-by battlefield tourist. Chalk that up to another reason I like to take people there. First, the entire battlefield can be seen in a few hours. Indeed, from the visitors center, you can see the bulk of the battlefield. And second, while the tactical maneuverings of the individual units were a bit complicated, from a larger perspective, one can lay out the battle in three phases, morning, mid-day, and afternoon.

Let me start with a quick overview. At the same time, I'll put in another plug for Stephen Sear's Landscape Turned Red. I've said it before, I think it is one of the finest of the many Civil War books out there, and if this blog entry sparks any additional interest in the battle, you will enjoy his story of the campaign and battle. My old paperback copy is well-worn.

Back to my story. The campaign actually begins outside of Richmond where Lee drives back McClellan's Union army in the Seven Day's Campaign. From there, Lee shifts the fighting north and defeats another Union army at Second Manassas (Bull Run) outside Washington, DC. Following the two victories (over McClellan and John Pope), Lee senses the time is right to invade the North, hoping to gather men and supplies and gain a strategic victory; one that will not just simply defeat a Union army on the field, but one that crushes an army on Northern soil, convinces the North the war is unwinnable, and is enough to persuade Britain and France the South deserves their recognition.

Off he goes across the Potomac. He thinks the Union Army of the Potomac is demoralized and disorganized after its latest defeat, so he anticipates having a considerable amount of time to stay north of the Potomac in Maryland and even Pennsylvania. Thus, he splits his army into several parts to forage, capture Harper's Ferry, and to watch the South Mountain passes for the Union Army. It is a dangerous decision; military theorists consider it a cardinal sin to split an army in the face of the enemy, particularly one no larger than Lee's, which at about 40,000 strong is well understrength due to straggling. Some 15-20,000 of his men are milling about in Virginia because they lack shoes, are worn out from campaigning, or simply decide they joined the Confederate Army not to invade the North, but to defend the South. A democratic army indeed.

McClellan follows with the more than 80,000 men of the Army of the Potomac. He has the good fortune to find a copy of Lee's orders splitting his army (this incident continues to spark "what if" historical writings) and sees an opportunity to crush Lee's army piecemeal. He moves faster than anticipated, though not quite fast enough, forcing Lee to begin concentrating his army sooner than he anticipated at the small village of Sharpsburg. Meanwhile, units of Lee's army defend the South Mountain passes to delay McClellan forces while the remainder of the army concentrates. Though he knows he is heavily outnumbered and for some reason (he does not know about the lost orders), McClellan is moving faster than anticipated, he aims to give battle on the heights outside of Sharpsburg with the Potomac River at his back. It is another daring--or foolish--move, done largely because Lee thinks he knows McClellan and does not want to leave Maryland without giving battle, despite the great odds. McClellan's army reaches the area on the 15th of September, but does not give battle until the morning of the 17th. Meanwhile, Harper's Ferry surrenders and Lee's army is able to concentrate fully, except for one division (about 5,000 soldiers) processing prisoners and captured equipment at Harper's Ferry.

The battle kicks off on the morning of the 17th with a large Union attack on Lee's left. It rages back and forth. Losses are heavy. Places like "The Cornfield," the East Woods, the West Woods, and the Dunker Church become places of great carnage and fame in Civil War history. Lee's left wing is battered and close to defeat. The Union attack is powerful, comprising two-and-a-half corps as opposed to about a corps for the Confederates. However, it is uncoordinated and conducted in piecemeal fashion. The Confederates are driven back, but Lee is able to hold on just barely by stripping units from his right wing to reinforce the left. He can shift forces around because McClellan does not mount an army-wide attack; he thinks Lee outnumbers him heavily and fears Lee is always on the verge of launching a killing counter-blow. He is also not a very good commander on the battlefield. By mid-morning, after three hours of some of the worst fighting Americans have ever seen, casualties for both sides exceed 10,000, units are exhausted, and the fighting shifts south....

To the Confederate center where the battle's second phase takes place. Here, the Confederate line is anchored on a road known locally as the "Sunken Road." By the end of the day, it will become known as the "Bloody Lane." Bitter fighting again rages as the Federal troops try to break the Confederate line. In about four hours of intense fighting, Union troops are able to drive the Confederates back, but they are exhausted in their victory. McClellan again does not send in more troops to exploit the advantage won at great cost. Instead, he shifts the army's focus further south. The Confederates, themselves exhausted, are thankful. They are running out of troops. Their lines are thin and makeshift. The only reinforcements available are the troops left at Harper's Ferry.

The last phase of the battle initially focuses on the Army of the Potomac's attempts to force its way across a bridge spanning Antietam Creek. It takes some four hours to do so and another two hours to get the troops re-formed after they cross the river. By late afternoon, they are ready, and a large Union force begins advancing on the town of Sharpsburg with few Confederates left to stop them. Lee's army is in danger of being driven from the field with the Potomac River at its back as Union units approach within a few hundred yards of the town. Then, almost miraculously, the lone Confederate division left at Harper's Ferry arrives on the field after a hard march of 17 miles. Its strength is reduced to about 3,000 due to straggling, but it goes into battle immediately and drives the Union forces back and the battle ends. (Side note: H and I once hiked 17 miles in one day, and we were certainly not ready to go into battle at the end of that long day!)

The two sides stare at each other the next day, but McClellan, who still outnumbers Lee greatly, refuses to attack. He has some 25,000 fresh infantry troops in two corps, plus a cavalry corps, but believes he is still outnumbered by Lee. Later in the day, Lee withdraws across the Potomac, his invasion over. He leaves behind 10,700 casualties, more than 25% of his army, and considerable Confederate strategic fortunes. Union losses are also heavy; some 12,400 out of about 50,000 engaged. Lincoln has a victory of sorts, but is greatly disappointed that McClellan did not destroy Lee's army.

So...back to the purpose of the blog entry. A few photos of the battlefield, both today and in 1862. Not much detail on the battle itself. For the blow-by-blow, check out the books on the battle by Stephen Sears, James McPherson, James Murfin, Jay Luvaas, or John Priest.

The Museum. It is small, but impressive. More about it in another blog entry.

| The battle. |

|

| Layout of the fighting on Confederate left flank that centered on the Cornfield. |

|

| When the fighting on the left flank died down from mutual exhaustion, the battle shifted to the Confederate center along the Sunken Road. |

|

| The Sunken Road as it looks today. Union soldiers attacked from the left, and they would suffer about 3,000 casualties trying to take it. |

| More Alexander Gardner photos taken a couple days after the fight. Showing the dead on a battlefield was a new concept, and the photos shocked the nation and the world. Many of these men were North Carolinians. |

| Union burial details collect the bodies. The Confederates suffered some 2,600 casualties defending the Sunken Road. |

|

| The view today from the Confederate positions. |

|

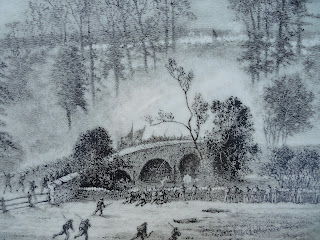

| Sketch of the final Union attack across the bridge by Edwin Forbes of Frank Leslie's Weekly. |

|

| Union vantage point. |

|

| After forcing the bridge, Burnside's men moved up this ridge... |

|

| But not our tour. Antietam Battlefield also contains a national cemetery, just outside the village of Sharpsburg. Elements of Burnside's units reached this area before retreating. |

|

| Soldiers from the Civil War.... |

|

| And other wars are buried here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment