T here with some photos of something I never thought I would see, the Mikasa, the only pre-dreadnought steel battleship still afloat. Unfortunately, I only had about an hour to wander over the ship, so my tour was a quick one. Plus, the weather was miserable; cold, wet, and windy. Later in the day, the area (Yokosuka), would see several inches of snow. Still, what a great way to spend a little time.

If you're not very familiar with the Mikasa, let me give you some background. The Mikasa served as the flagship of Admiral Togo Heihachiro during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, which included several naval engagements, including one of the most decisive and famous naval battles in history, the Battle of the Tsushima Strait, where the Imperial Japanese Navy annihilated an entire Russian fleet. This was history's only decisive sea battle fought by modern steel battleship fleets. In a two-day engagement, the Russians lost 11 battleships and four cruisers sunk, captured, or scuttled by their crews. More ships were interned in neutral countries. The Russians also suffered over 10,000 casualties, including 4300 killed, almost 6,000 captured, and another 1800 interned. The Japanese lost a handful of torpedo boats, a little over 100 killed, and another 500 wounded. The victory was a humiliation for the Russians and effectively ended the war.

In addition to being a fascinating snapshot of a bygone era of naval warfare, the Mikasa also represents a period in the history of Northeast Asia that still reverberates today in the affairs and attitudes of the countries of the region. The period saw Japan, China, and Russia all trying to establish dominance over the Korean peninsula. The Qing Dynasty of China and Meiji Japan fought a war over Korea in 1894-95, with Tokyo emerging victorious and the Chinese forced to relinquish control of Korea. The 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War also grew out of rivalry over Korea, as well as Manchuria. The Japanese victory over a major European power shocked the Western world, put Japan on the world stage as a power to be reckoned with, and catapulted the country into a period of expansionism which would end with its total defeat in 1945.

Built by the British in the late 1890s because at the time the Japanese could not produce their own battleships, and commissioned in 1902, the Mikasa was a powerful ship for the time. She was 432-feet long, displaced slightly over 15,000 tons, and had a crew of 830. Her main battery consisted of four 12-inch/40 caliber guns mounted in two turrets, one fore and one aft. The secondary armament comprised 14 6-inch/45 caliber quick-firing guns mounted in casemates, mostly along the hull.

After the Russo-Japanese war, the Mikasa had an interesting career. Just six days after the peace treaty was signed, the ship's magazine caught fire and exploded while the ship was moored in Sasebo harbor, sinking her and killing 251 sailors. The Mikasa was refloated, repaired, and restored to active service in 1908. By then, however, the ship was already made obsolete by the development by the British of the all big gun dreadnought class battleship, which would dominate the seas until the advent of the aircraft carrier in World War Two. The Mikasa was relegated to the role of coastal defense until decommissioned in 1923. Following the signing of the Washington Naval Treaty, which limited the numbers, sizes, and types of warships for Britain, the US, and Japan, the Mikasa was scheduled for destruction. The signatories of the treaty, however, agreed to allow the Japanese to keep the Mikasa as a memorial ship. With the Japanese surrender to the US and its allies in 1945, the Mikasa was stripped of all her armaments and allowed to deteriorate. However, a campaign led by the Japan Times, supported by the Japanese government, and endorsed by US Admiral Chester Nimitz of WW2 fame led to her restoration in 1961. Since then, the ship has been on display in Yokosuka Harbor, just a few hundred yards from ships of the US 7th Fleet--a modern day visual reminder of the region's security dynamics.

|

| Admiral Togo, one of the most famous military figures in Japanese history. |

|

| Secondary armament of quick-firing 6 inch guns. |

|

| Stern 12-inch battery. During the Battle of the Yellow Sea in August of 1904, this turret was struck twice by Russian shells, knocking it out and causing 125 casualties. |

|

| 12-pounders mounted on the upper deck. |

|

| Armored conning tower. |

|

| Fore mounted 12-inch gun turret. |

|

| Chart room. |

|

| The view for the ship's captain and Admiral Togo. |

|

| Wireless room. |

|

| 6-inch gun room. |

|

| 6-inch gun crew in action. Imagine the noise and smell of cordite in this room when the gun fires. The assault on the senses must have been tremendous. |

The main deck of the ship has been turned into a museum with lots of relics of the ship, paintings, photos, and videos. It was well done and offered a considerable amount of English for those like me who cannot read Japanese.

|

| The Mikasa in her glory days. |

|

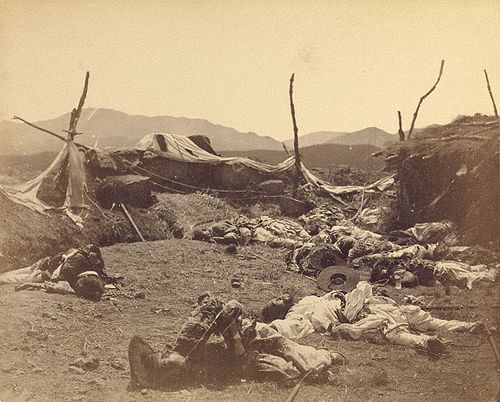

| Siege of Port Arthur, one of the main Japanese objectives of the 1904-1905 war. The naval battles were certainly more sexy, but the majority of the fighting took place on land. There were major battles fought around Port Arthur and on the plains of Manchuria, including one battle (Mukden) that was the largest ever fought prior to World War One. |

|

| Japanese landing on the Liaodong Peninsula. From here, the Japanese land forces would turn south to lay siege to Port Arthur. |

|

| The land campaign. |

|

| Sailors cleaning the decks. Could have been a photo of any US ship of the period. |

|

| Lovely living quarters. |

|

| Uniforms of Admiral Togo. He's as famous in Japan as George Patton is in the US. |

|

| Togo on the Mikasa during the Battle of the Tsushima Strait. |

|

| The man himself. |

Other shots.

|

| A nod to other great ships in naval history. This is a model of the HMS Victory, Admiral Horatio Nelson's flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. It sits moored in Portsmouth, England, and is worth a visit if you are ever in the UK. |

|

| USS Constitution. |

|

| The bowels of the ship were not open to the public, thus the photograph of the engine that once powered the Mikasa. The ship had two of these vertical three cylinder triple-expansion reciprocating steam engines, one for each screw. The Vickers- made engines used steam generated by 25 coal-fired boilers. They were rated at 15,000 horsepower, providing the ship a top speed of just over 18 knots (21 mph). |

|

| Diagram of the 12-inch gun turret. |

|

| Captain's quarters. |

|

| Admiral's saloon with a 12-pounder cannon in the background. |

|

| Admiral's quarters. |

|

| Aft gun turret. |

|

| Shells for the 12-inch guns. |

|

| Shot of the stern with the flag of Imperial Japan. |

|

| Shot of the Mikasa on a much more sunny day. |

If you want to read more about the Battle of the Tsushima Strait, the Russo-Japanese War, and the period itself, I recommend

The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905 by Denis and Peggy Warner. The book was written in 1974, but in my view is still the finest English account of the era out there.